Why does Southwark need low traffic neighbourhoods?

- What are low traffic neighbourhoods?

- Why do we need low traffic neighbourhoods? Four reasons

- These problems can be solved by LTNs

What does research and data show?

- People walk and cycle more in LTNs

- LTNs reduce overall traffic volume and car ownership

- LTNs improve road safety

- LTNs see reductions in street crime

- Emergency service response times are not negatively impacted

Questions about LTNs

- Who benefits from LTNs?

- How do LTNs impact disabled people?

- Will car journeys take longer?

- What about the high street?

- What about resident exemptions?

- What about timed closures?

- Why isn’t air quality being monitored?

- What is a bus gate?

- What if I live on a main road?

- Are LTNs popular?

- Who came up with this idea?

LTN Trials in Southwark

- How do the trials work?

- Current trials in Southwark

- I live in a different part of Southwark – when is it my turn?

Why does Southwark need low traffic neighbourhoods?

What are low traffic neighbourhoods?

A low traffic neighbourhood is a network of streets from which “through” motor traffic has been removed – this means traffic travelling through an area, not accessing a residence inside it. It is usually a whole area, bordered by A-roads, railways or other boundaries, rather than one or two streets. Every street is still accessible by vehicle, but barriers like bollards, planters or ‘camera gates’ prevent vehicles taking a short cut across the area.

Low traffic neighbourhoods, LTNs for short, have been found to increase walking and cycling, make streets safer, and reduce driving and car ownership.

Why do we need low traffic neighbourhoods? Four reasons

1. Too many motor vehicles dominate our roads

In 2019 there were over 30,000 injuries reported due to road traffic collisions in London. Of those 3,780 were serious and there were 125 deaths due to road violence. Motor vehicle traffic is also a major contributor to air pollution which results in an estimated 9,500 early deaths per year in London.

Transport accounts for 25% of carbon emissions in Southwark. Southwark Council has declared a Climate Emergency and must reduce the number of motor vehicles on our streets urgently. We are already seeing impacts due to climate change so radical change is needed. Due to their high carbon cost, electric vehicles can only be a small part of the solution.

In Southwark, 60% of households do not have access to a car, which is skewed towards people on lower incomes, yet groups that do not have access to a car are most likely to be harmed by them. Disabled people and those with health conditions make 32% fewer car trips in London, yet as pedestrians, disabled people are five times as likely to be injured by a driver than non-disabled people.

Motor traffic has risen steeply in the last ten years across the country, and Southwark is no exception. Between 2013 and 2019, the number of miles driven on Southwark’s roads rose by 68.8 million miles or 15%.

2. Traffic has risen most on minor roads

While the number of miles driven on A and B roads in London has actually fallen slightly in the last ten years, on C or unclassified roads it’s risen by a massive 72% – most likely due to sat navs directing drivers away from main roads.

Source: Department for Transport

3. Too much traffic on minor roads is dangerous

Minor streets aren’t designed to carry lots of traffic. Blind corners and few crossings means speeding in particular has a great impact. Minor roads are more dangerous for main roads, particularly for children.

Each mile driven on a minor urban road, results in 17% more killed or seriously injured pedestrians than a mile driven on an urban A road.

Specifically, on urban roads, driving a mile on a minor urban road is twice as likely to kill or seriously injure a child pedestrian, and three times more likely to kill or seriously injure a child cyclist, compared to driving a mile on an urban A road.

Source: Dr Rachel Aldred

TfL has recently found that while overall road casualties have decreased, there has been an increase for people walking and cycling and this increase is increasing at almost double the rate on minor roads.

Source: TfL Travel in London Report 13 (p205)

4. Too much traffic on minor roads stops people walking & cycling

Our traffic-heavy streets put people off walking or cycling, especially more vulnerable groups like children and the elderly. Road danger and too much traffic are cited as the greatest barrier to people cycling more.

Source: TfL Attitudes toward cycling report (p46, 56)

The solution to this is either protected space for cycling or reducing motor traffic volume. TfL and the DfT have guidance that suggests traffic needs to be below certain levels for people to cycling without protected space. It would not be practical to build protected cycling lanes on every minor road in Southwark and this would not benefit people walking, since traffic volume impacts those trips as well.

A third of Londoner’s car journeys are 2km or less, a distance that could be walked in 25 minutes. Two-thirds of trips are less than 5km and can be cycled in under 20 minutes. Distance is not what prevents most Londoners from walking and cycling.

This lack of physical activity is having a catastrophic effect on the nation’s health – cancer, heart disease and depression are all linked to sedentary lifestyles. Southwark is no different – our children have one of the worst rates of childhood obesity in the UK.

These problems can be solved by low traffic neighbourhoods

Low traffic neighbourhoods have three outcomes, 1) they stop rat running motor vehicles, returning through traffic to the strategic road network (unless they are accessing the neighbourhood, 2) they reduce short car trips made by local residents, and they 3) create space for walking, cycling, scooting and wheeling.

LTNs can can reduce vehicles inside the area by 50-90%, creating a quiet network of streets where anyone can walk, cycle or use their wheelchair in the middle of the road. They enable active travel, healthy lifestyles, less car use, fewer injuries and deaths, cleaner air and fewer carbon emissions.

They are not a substitute for other measures including pollution and speed control measures, and main road interventions including protected cycleways and bus lanes, but with 91% of people in London living on minor roads (this varies little by age, gender, income, disability and ethnicity), LTNs will play a key role in transforming Southwark. Read on to find out more.

Photo credit: Crispin Hughes

What does research and data show?

People walk and cycle more in LTNs

By providing a safer environment LTNs enable more people to walk and cycle. Waltham Forest’s first low traffic neighbourhoods were implemented in 2015 so there has been time to study them in detail. Residents within an LTN walked 115 minutes more per week and cycled 20 minutes more. This was much larger than in areas that received other walking and cycling schemes without LTNs. King’s College London also found that increased active travel leads to longer life expectancy for residents in Waltham Forest.

Hackney saw similar results in the 10 years between 2001 and 2011 when it implemented low traffic neighbourhoods and installed modal filters. Cycling trips more than tripled in this time.

Manual counts were taken to gauge the impact of the Dulwich Village modal filters on cycling levels. The estimated number of school children cycling increased by seven times compared to a much smaller increase in a control site. There was also a higher proportion of women cycling compared to the control site.

Lambeth found that cycling increased by 51% within the Railton LTN and 32% across the area. Additionally it increased by 65% and 84% on Railton Road and Shakespeare Road, two through roads that are now filtered.

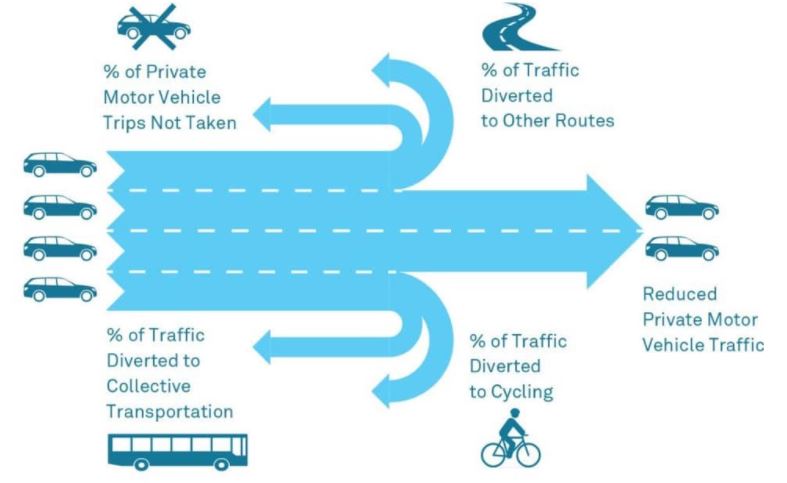

LTNs reduce traffic volume and car ownership

Evidence from Hackney and Waltham Forest shows that low traffic neighbourhoods reduce car journeys and car ownership. Traffic is not just displaced and overall traffic in the area drops. This may take some time as when new schemes go in it takes time for them to bed in. People get used to the changes and GPS apps update. Over time some people also change their mode of travel and switch car trips to walking and cycling ones.

While some car journeys will take alternative routes this must be viewed in the context of traffic only increasing on minor roads in the last decade as shown above. From a traffic management standpoint it is also much more difficult to manage traffic if it avoids signalised crossings by taking back routes.

There are some claims that LTN trials have increased congestion on boundary roads. It’s important to note that traffic has increased all across London since Covid-19 due to less people taking public transportation, but while we wait for Southwark to release monitoring data, we’ve heard from residents that traffic near these schemes is no worse than it was prior to them being implemented. Both Lambeth and Hackney have released monitoring on LTNs as part of their Covid-19 transport response. They found LTNs did not increase overall traffic on surrounding main roads. Additional monitoring in Lambeth has shown a 31% decrease in traffic and 23% decrease in HGVs in and around the Railton LTN.

In addition to cycling tripling in Hackney, car journeys also halved in the 10 years the council implemented LTNs and modal filters. In Waltham Forest traffic levels fell by 56% on roads within the LTN with a 16% drop overall resulting in 10,000 motor car journeys disappearing.

This is due to traffic evaporation. By reducing road capacity for motor vehicles, traffic decreases. This has been seen in many places around the world. When walking and cycling are made more safe and convenient, and driving slightly less convenient for short trips, fewer people choose to get in their cars. Some people will stop making particular trips, combine multiple trips into one, change destination, travel at a less congested time, or switch to public transport, walking or cycling.

King’s College London also found that Waltham Forest’s low traffic neighbourhoods reduced air pollution. Another study showed a dramatic drop in illegal air quality levels, including on main roads.

It was also found that car ownership within LTNs dropped 6% after two years. This was much larger than other areas where other walking and cycling schemes were implemented. Surveys have also been done that also show evidence of lower car ownership after an LTN is implemented.

LTNs improve road safety

By reducing traffic volume, road safety within an LTN improves. As mentioned above, motor traffic on minor roads is more dangerous than main roads, and collisions on minor roads have been increasing at a much higher rate than on major roads according to TfL.

In Waltham Forest there was a 70% reduction in road traffic injury per trip on roads within the LTN for people walking, cycling and in motor vehicles. There was also no negative impact on boundary roads.

Many main road collisions occur at junctions with minor roads. Removing rat running traffic reduces these junction movements making them safer. Modal filters placed at junctions with main roads eliminate all motor traffic movements.

Modal filters in East Dulwich

LTNs see reductions in street crime

Waltham Forest saw a 10% reduction in street crime within their LTNs and a larger decrease in violent crime. No displacement to other areas was found. This could perhaps be due to more eyes on the street, an idea Jane Jacobs popularised in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. This requires neighbourhoods that encourage people to be out on the street, not ones that just have passing cars.

Emergency service response times are not negatively impacted

Emergency services are statutory consultees to all highway schemes, including low traffic neighbourhoods. Every street within an LTN is also accessible by emergency vehicles. Schemes are also adjusted based on input from emergency services as was seen in Walworth when some filters were changed to be camera enforced.

Freedom of information act requests to ambulance service trusts in the UK, including London, have revealed that low traffic neighbourhoods, popup cycle lanes and other walking and cycling schemes have not hindered ambulance response times. Four trusts, including London, expressed explicit support for active travel schemes. Additionally, the London Fire Bridge has stated that they have not noticed any impacts due to LTNs implemented in 2020 in their annual Fire Facts report.

In Waltham Forest response times within the LTN were unchanged and became slightly faster on boundary roads. The Borough Commander stated, “It is my view that this data does not show an increase in response times and therefore that the road closures in Waltham Forest have not had a significant impact on our services”.

Average response times of fire appliances

Many NHS Trusts in London have come out in support of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods due to the numerous health benefits they bring. Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity is funding 3 LTNs in Southwark, in Brunswick Park, North Peckham and East Faraday. These schemes benefit schools in the area with goals to promote active travel among pupils.

Questions about LTNs

Who benefits from LTNs?

Low traffic neighbourhoods benefit most of us by reducing motor vehicle use and making walking safer, which is the most used mode of travel in London. A recent study has shown LTNs rolled out since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic have been equitable, with people living in deprived areas were much more likely to live in a new LTN than people in less deprived areas, including in Southwark. LTNs particularly benefit people who do not have access to a car by giving them more transportation options. Black Londoners are less likely to have a car in their household than white Londoners. People on lower incomes are also much less likely to have household access to a car – 58% of low-income Londoners do not have access to a car. This will be greater in Southwark which has a higher proportion of low-income households and lower car ownership levels than London as a whole.

The negative impacts of motorised transport disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups. This includes transport-related air pollution, climate change and traffic collisions. For example, Black children in London are more at risk from pedestrian injury than white or Asian children.

Women also stand to benefit from low traffic neighbourhoods. Women make many journeys beyond typical commuting trips. Women in London are three times more likely to drop off children at school than men. Low traffic neighbourhoods make local trips, including school drop offs, shopping trips and visits to friends and family safer and more pleasant.

Low traffic neighbourhoods don’t only benefit people living within them. While 91% of people in London live on minor roads, even people that don’t will benefit from safer travel routes through LTNs and from safer junctions along boundary roads. When considering age, gender, income, disability and ethnicity there is little variation between residents living on minor roads and main roads.

That being said, LTNs do provide many benefits for those living within them. Reducing traffic has been shown to boost communities in neighbourhoods; low traffic means more people are likely to consider their neighbours as friends. This was famously studied by Donald Appleyard and the thesis was reconfirmed by researchers in Bristol in 2011.

The council is not able to roll out LTNs in every Southwark community at once, so some will get LTNs before others. One way to get an LTN in your area is to join us in campaigning for one.

How do LTNs impact disabled people?

Impacts on disabled people must be considered when implementing LTNs and disabled people must be included in the engagement process. LTNs can bring many positive changes for disabled people, just like they do for everyone else.

Reducing the amount of traffic on minor streets reduces collisions and increases safety for people walking, including disabled people. Walking, including wheeling, is the most common mode of transportation for disabled people in London.

Disabled people are less likely to have access to a car than non-disabled people. Over half of disabled Londoners (52%) do not have household access to a car compared to 34% for non-disabled Londoners. The proportion who drive a car is 28% compared to 45% for non-disabled people, and as passengers the rates are the same. Disabled Londoners are also less likely to have a driving license (40% vs. 68%).

17% of disabled Londoners sometimes use a cycle to get around compared to 18% of non-disabled Londoners, and around three quarters of disabled cyclists use their cycle as a mobility aid, and find cycling easier than walking. Disabled people who cycle benefit from an LTN in the same was as non-disabled people who cycle: less motor traffic, quieter and safer streets and easier routes around their neighbourhood.

Anyone who needs to travel by car or taxi can still do so in an LTN, so for those who rely on motor vehicles, they will still be able to make their journeys. For people that do need to drive, traffic reduction measures, along with LTNs, will result in less congestion and allow for quicker journeys.

What about the high street?

Low traffic neighbourhoods with bordering high streets will make it easier and more pleasant for people to walk or cycle to their nearest shops. Lower traffic levels benefit local businesses through an increase in sales by local customers, and higher spending by people who walk or cycle to a high street. There is plenty of evidence that good walking/cycling access to shops is good for business.

Source: Walking and Cycling: the economic benefits

What about resident exemptions?

LTNs reduce driving trips by making them slightly less convenient (and active travel much more accessible). Exceptions for residents would not achieve this and create a type of gated community by giving residents with permits special access. This could actually encourage more short driving trips as residents wouldn’t face competition for road space from non-local drivers.

This increase in traffic would prevent people from walking and cycling as traffic volume could still be too high. Additionally, these schemes use ANPR cameras and non-permitted drivers still go through them (despite being issued a fine) which results in more traffic. This also precludes a pocket park and other ways the space can be used.

What about timed closures?

We do not advocate for timed closures. A neighbourhood should not be safe for only some of the time. Traffic levels can still be high during off-peak hours that will keep people from walking and cycling. As mentioned above, planters, bollards and permanent filters are also preferable to camera closures since they lead to lower compliance, although these may be necessary for some streets for emergency and refuse vehicle access.

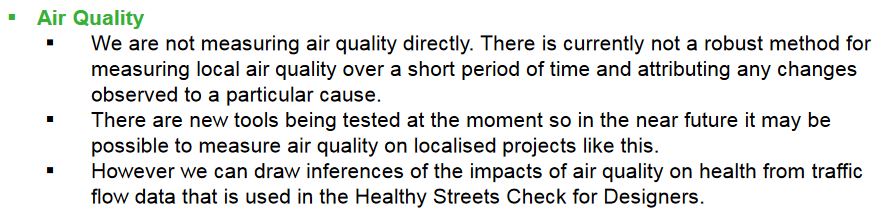

Why isn’t air quality being monitored?

Some LTN trials, including the three funded by Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity do not include air quality monitoring. As explained by Lucy Saunders, a transportation processional working with Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity on the schemes, there is not currently a robust method for measuring local air quality over a short period of time attributing any changes observed to a particular cause.

Southwark Council has also given this explanation for other current schemes. The Greater London Authority warns that improvements in air quality can be difficult to detect without long-term studies and multi-year analysis (p14).

Southwark Council has also given this explanation for other current schemes. The Greater London Authority warns that improvements in air quality can be difficult to detect without long-term studies and multi-year analysis (p14).

What is a bus gate?

A bus gate is not a real gate but a sign-posted point on the road that bans motor vehicles (excepting buses and emergency services) from passing. Cameras monitor motorists’ license plates and trigger penalty notices. Bus gates have been introduced in areas where it would be inappropriate for a high volume of through traffic, such as residential areas, but which are heavily reliant on public transport.

A bus gate prioritises sustainable transport, opening up the street for families to cycle to school as well as commuters to work, forming the backbone of a healthy low traffic neighbourhood. Filters could be needed on surrounding streets to prevent traffic displacement.

What if I live on a main road?

Better Streets for Southwark also campaigns for healthy main roads, which are places where people shop, travel and live. It would not be practical to remove motorised traffic altogether from major through routes, but they can be made safer and traffic can be reduced on them. We would like to see:

- a 20mph speed limit on all roads in Southwark

- more and better pedestrian crossings

- better, wider pavements

- safe space to cycle

- seating, greenery, shelter

We also support ULEZ and would like to see smart road user prices implemented in London. Low traffic neighbourhoods are a step towards reducing overall volumes of motor traffic, not just on minor streets. We hope that the effect they have on encouraging people not to drive short journeys will benefit all of Southwark’s roads in the long term.

Are LTNs popular?

The short answer is yes. Polls and surveys have shown the majority of people support LTNs, even in areas where there was opposition in the past. In Waltham Forest when work first started on the LTN 44% of people were opposed. Five years later, just 1.7% said they’d like to scrap the scheme. When local elections came around after the LTN was implemented councillors that supported the scheme saw a significant increase in votes.

A January 2021 poll found that 63% of people living within an LTN say it’s improved their lives and 47% not living in an LTN think it would improve their lives, compared to 14% for both groups. Polls have also found majority support for LTNs both in London and nationally.

Who came up with this idea?

Low Traffic Neighbourhoods are nothing new. Many Local Authorities in England started installing LTN’s since the arrival of the motor car in the late 1890’s. Many estates in the UK have also been built on low traffic principles. There are also many historic filters in London (and Southwark). Hackney also filtered many streets between 2001 and 2011, which tripled cycling and halved car trips. Recently, there has been a renewed focus on LTN’s during the Covid-19 pandemic as many started using walking and cycling as their main mode of transport.

Elsewhere in Europe, planners no longer design roads where people live or shop to be through routes for motor traffic. This has been a mainstay of Dutch transport planning (called ‘unbundling’) and has contributed to high levels of cycling and cycle safety in the Netherlands. Low traffic neighbourhoods in London (such as Hackney, Waltham Forest) and elsewhere are inspired by Dutch cities and stand alongside approaches such as Barcelona’s “Superblocks”.

LTN Trials in Southwark

How do the trials work?

In it’s transport response to Covid-19, Transport for London and Southwark Council launched their Streetspace programmes to enable more walking and cycling while public transportation capacity was reduced. These changes also coincided with the Mayor’s and Southwark Council’s plans to reduce car use and increase healthy, active travel. Along with protected cycle lanes and widened footways, Southwark Council has been implementing low traffic neighbourhoods using experimental traffic orders. By trialing these changes residents experience what it’s like living within a low traffic neighbourhood during the engagement and consultation process without doing expensive road works. Adjustments can be made to the scheme based on input from residents, businesses and emergency services during the trial as has been done in the Walworth LTN. Usually a formal consultation is held after the scheme has been in place between 6 months and a year and a decision is made whether the LTN will be made permanent within 18 months.

This means if you like schemes near you, you must make it known. One downside of a trial is that many people will like the changes but think they are a done deal so they will not proclaim their support. Meanwhile people opposed to these changes are very motivated to let that be heard.

Current trials in Southwark

Southwark has currently implemented 6 low traffic neighbourhoods. We are creating resources specific to each scheme. For now we have linked to the Commonplace maps where you can share your views with Southwark Council.

These schemes will need your support to be made permanent. If you like these changes, email your councillors to let them know!

- Brunswick Park

- Dulwich Village*

- East Dulwich

- East Faraday

- Great Suffolk Street

- North Peckham

- Walworth

Note*: Although we wouldn’t consider the Dulwich Village scheme a true LTN due to it not eliminating some through routes and relying on timed closures for much of the scheme, it has transformed the area and deserves to be mentioned here.

I live in a different area – when is it my turn?

The Department for Transport is releasing a second round of funding that will be available to councils. This may lead to more Streetspace projects in Southwark, including LTNs. If you’d like an LTN in your area, contact us, and we can help you campaign for one. Email us at hello@BetterStreetsForSouthwark.org.uk.

Credit to Possible and Better Streets for Enfield for their great guides that much of this borrows from.